Web scraping using Python and Scrapy

Overview

Teaching: 90 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

How can scraping a web site be automated?

How can I setup a scraping project using the Scrapy framework for Python?

How do I tell Scrapy what elements to scrape from a webpage?

How do I tell Scrapy to follow URLs and scrape their contents?

What to do with the data extracted with Scrapy?

Objectives

Setting up a Scrapy project.

Understanding the various elements of a Scrapy projects.

Creating a spider to scrape a website and extract specific elements.

Creating a two-step spider to first extract URLs, visit them, and scrape their contents.

Storing the extracted data.

The material in this section was adapted for the NYU Library Carpentries workshop (November, 2020) by Alexandra Provo.

Recap

Here is what we have learned so far:

- We can use XPath queries to select what elements on a page to scrape.

- We can look at the HTML source code of a page to find how target elements are structured and how to select them.

- We can use the browser console and the

$x(...)function to try out XPath queries on a live site. - We can use the Scraper browser extension to scrape data from a single web page. Its interface even tries to guess the XPath query to target the elements we are interested in.

This is quite a toolset already, and it’s probably sufficient for a number of use cases, but there are limitations in using the tools we have seen so far. Scraper requires manual intervention and only scrapes one page at a time. Even though it is possible to save a query for later, it still requires us to operate the extension.

Introducing Scrapy

Enter Scrapy! Scrapy is a framework for the Python programming language.

A framework is a reusable, “semi-complete” application that can be specialized to produce custom applications. (Source: Johnson & Foote, 1988)

In other words, the Scrapy framework provides a set of Python scripts that contain most of the code required to use Python for web scraping. We need only to add the last bit of code required to tell Python what pages to visit, what information to extract from those pages, and what to do with it. Scrapy also comes with a set of scripts to setup a new project and to control the scrapers that we will create.

It also means that Scrapy doesn’t work on its own. It requires a working Python installation (Python 2.7 and higher or 3.4 and higher - it should work in both Python 2 and 3), and a series of libraries to work.

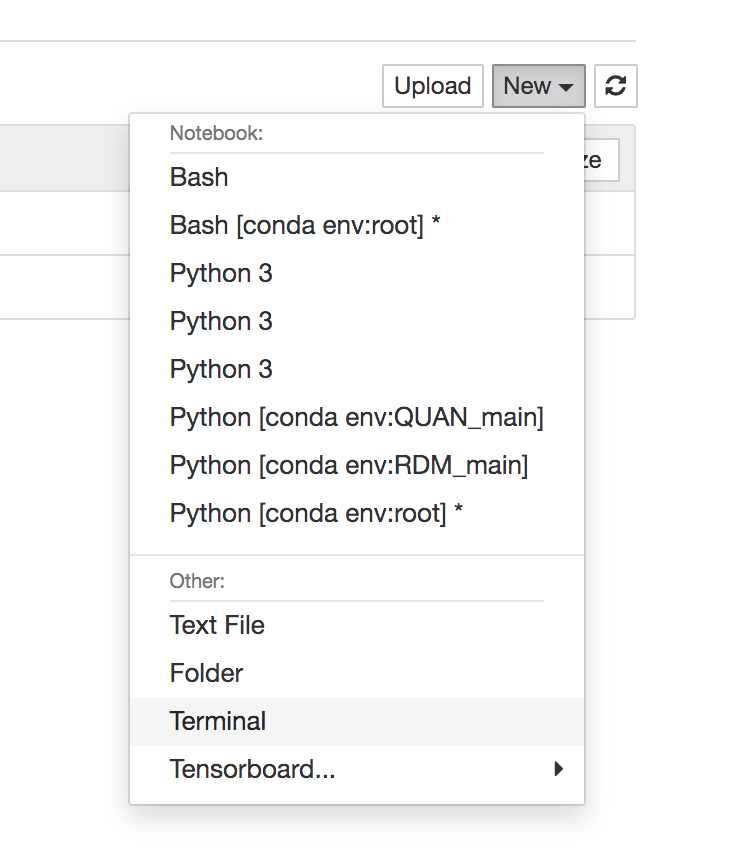

Today, we’ll be using NYU’s JupyterHub. Once you’ve logged in, start a terminal by navigating to New–>Terminal on the top right.

This will open a new tab in your browser. Set your Python environment to the one with Scrapy installed by typing the following:

conda activate RDM_main

If you are working locally on your own machine, and if you haven’t installed Python or Scrapy yet, you can refer to the setup instructions. If you install Scrapy as suggested there, it should take care to install all required libraries as well.

You can verify that you have the latest version of Scrapy installed by typing

scrapy version

in a shell. If all is good, you should get the following back:

Scrapy 2.4.0

If you have a newer version, you should be fine as well.

To introduce the use of Scrapy, we will depart from our previous examples and work with an NYU website. We will start by scraping a list of URLs from the list of NYU IFA faculty members and then visit those URLs to scrape detailed information about those faculty members.

Setup a new Scrapy project

The first thing to do is to create a new Scrapy project.

If you’re using JupyterHub, we can get started right away. If you are working locally on your machine, navigate first to a folder on your drive where you want to create our project (refer to Software Carpentry’s lesson about the UNIX shell if you are unsure about how to do that). Then, type the following

scrapy startproject ifafaculty

where ifafaculty is the name of our project.

Scrapy should respond will something similar to (the paths will reflect your own file structure)

New Scrapy project 'ifafaculty', using template directory '/opt/conda/envs/RDM_main/lib/python3.7/site-packages/scrapy/templates/project', created in:

/home/jovyan/ifafaculty

You can start your first spider with:

cd ifafaculty

scrapy genspider example example.com

If we list the files in the directory we ran the previous command

ls -F

we should see that a new directory was created:

ifafaculty/

(alongside any other files and directories you had lying around previously). Moving into that new directory

cd ifafaculty

we can see that it contains two items:

ls -F

ifafaculty/ scrapy.cfg

Yes, confusingly, Scrapy creates a subdirectory called ifafaculty within the ifafaculty project

directory. Inside that second directory, we see a bunch of additional files:

ls -F ifafaculty

__init__.py items.py settings.py

__pycache__ pipelines.py spiders/

We will introduce what those files are for in the next paragraphs. The most important item is the

spiders directory: this is where we will write the scripts that will scrape the pages we

are interested in. Scrapy calls such scripts spiders.

Creating a spider

Spiders are the business end of the scraper. It’s the bit of code that combs through a website and harvests data. Their general structure is as follows:

- One or more start URLs, where the spider will start crawling

- A list of allowed domains to constrain the pages we allow our spider to crawl (this is a good way to avoid mistakenly writing an out-of-hand spider that mistakenly starts crawling the entire Internet…)

- A method called

parsein which we will write what data the spider should be looking for on the pages it visits, what links to follow and how to parse found data.

To create a spider, Scrapy provides a handy command-line tool:

scrapy genspider <SCRAPER NAME> <START URL>

We just need to replace <SCRAPER NAME> with the name we want to give our spider and <START URL> with

the URL we want to spider to crawl. First, make sure you are in the top level ifafaculty folder. Then, we can type:

scrapy genspider ifabios www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm

This will create a file called ifabios.py inside the spiders directory of our project.

Let’s open that file. If you’re using JupyterHub, toggle back to your “Home” tab (making sure not to close the browser tab with your terminal window) and open the file. If you are working locally on your machine, you can open this file in your favorite text editor, for example SublimeText or TextEdit. It should look something like this:

import scrapy

class IfabiosSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = 'ifabios'

allowed_domains = ['www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm']

start_urls = ['http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm/']

def parse(self, response):

pass

Here is this same script, but marked up with comments that explain what each line means:

import scrapy

class IfabiosSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "ifabios" # The name of this spider

# The allowed domain and the URLs where the spider should start crawling:

allowed_domains = ['www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm']

start_urls = ['http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm/']

# And a 'parse' function, which is the main method of the spider. The content of the scraped

# URL is passed on as the 'response' object:

def parse(self, response):

pass

Don’t include

http://when runningscrapy genspiderThe current version of Scrapy apparently only expects URLs without

http://when runningscrapy genspider. If you do include thehttpprefix, you might see that the value instart_urlin the generated spider will have that prefix twice, because Scrapy appends it by default. This will cause your spider to fail. Either runscrapy genspiderwithouthttp://or amend the resulting spider so that it looks like the code above.

Object-oriented programming and Python classes

You might be unfamiliar with the

class IfabiosSpider(scrapy.Spider)syntax used above. This is an example of Object-oriented programming.All elements of a piece of Python code are objects: functions, variables, strings, integers, etc. Objects of a certain type have certain things in common. For example, it is possible to apply special functions to all strings in Python by using syntax such as

mystring.upper()(this will make the contents ofmystringall uppercase).We call these types of objects classes. A class defines the components of an object (called attributes), as well as specific functions, called methods, we might want to run on those objects. For example, we could define a class called

Petthat would contain the attributesname,colour,ageetc. as well as the methodsrun()orcuddle(). Those are common to all pets.We can use the Object-oriented paradigm to describe a specific type of pet:

Dogwould inherit the attributes and methods ofPet(dogs have names and can run and cuddle) but would extend thePetclass by adding dog-specific things like apedigreeattribute and abark()method.The code in the example above is defining a class called

IfabiosSpiderthat inherits theSpiderclass defined by Scrapy (hence thescrapy.Spidersyntax). We are extending the defaultSpiderclass by defining thename,allowed_domainsandstart_urlsattributes, as well as theparse()method.

The

SpiderclassA

Spiderclass will define how a certain site (or a group of sites, defined instart_urls) will be scraped, including how to perform the crawl (i.e. follow links) and how to extract structured data from their pages (i.e. scraping items) in theparse()method.In other words, Spiders are the place where we define the custom behaviour for crawling and parsing pages for a particular site (or, in some cases, a group of sites).

Once we have the spider open in a text editor, we can start by cleaning up a little the code that Scrapy has automatically generated.

Paying attention to

allowed_domainsLooking at the code that was generated by

genspider, we see that by default the entire start URL has ended up in theallowed_domainsattribute.Is this desired? What do you think would happen if later in our code we wanted to scrape a page living at the address

https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/special-appointments.htm?Solution

allowed_domainsis a safeguard for our spider, it will restrict its ability to scrape pages outside of a certain realm. An URL is structured as a path to a resource, with the root directory at the beginning and a set of “subdirectories” after that. Inwww.mydomain.ca/house/dog.html,http://www.mydomain.ca/is the root,house/is a first level directory anddog.htmlis a file sitting inside thehouse/directory.If we restrict a Scrapy spider with

allowed_domains = ["www.mydomain.ca/house"], it means that the spider will be able to scrape everything that’s inside thewww.mydomain.ca/house/directory (including subdirectories), but not, say, pages that would be inwww.mydomain.ca/garage/. However, if we setallowed_domains = ["www.mydomain.ca/"], the spider can scrape both the contents of thehouse/andgarage/directories.To answer the question, leaving

allowed_domains = ["www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm"]would restrict the spider to pages with URLs of the same pattern, andhttps://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/special-appointments.htmif of a different pattern, so Scrapy would prevent the spider from scraping it.How should

allowed_domainsbe set to prevent this from happening?Solution

We should let the spider scrape all pages inside the

www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/domain by editing it so that it reads:allowed_domains = ["www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/"]

Let’s go back to our ifabios.py file and make sure to set the allowed domain to be more encompassing. In this case, we’ll also want to remove a trailing slash at the end of the start_url.

import scrapy

class IfabiosSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "ifabios"

allowed_domains = ["www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/"]

start_urls = ['http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm']

def parse(self, response):

pass

Don’t forget to save the file (File–>Save in the JupyterHub dropdown menu) once you have made these changes.

Running the spider

Now that we have a first spider setup, we can try running it. Going back to the Terminal, we first make sure

we are located in the project’s top level directory (where the scrapy.cfg file is) by using ls, pwd and

cd as required, then we can run:

scrapy crawl ifabios

Note that we can now use the name we have chosen for our spider (ifabios, as specified in the name attribute)

to call it. This should produce the following result

2020-11-02 23:56:38 [scrapy.utils.log] INFO: Scrapy 2.4.0 started (bot: ifafaculty)

...

2020-11-02 23:56:38 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm> (referer: None)

2020-11-02 23:56:38 [scrapy.core.engine] INFO: Closing spider (finished)

2020-11-02 23:56:38 [scrapy.statscollectors] INFO: Dumping Scrapy stats:

{'downloader/request_bytes': 553,

'downloader/request_count': 2,

'downloader/request_method_count/GET': 2,

'downloader/response_bytes': 7681,

'downloader/response_count': 2,

'downloader/response_status_count/200': 2,

'elapsed_time_seconds': 0.343902,

'finish_reason': 'finished',

'finish_time': datetime.datetime(2020, 11, 3, 4, 56, 38, 692245),

'log_count/DEBUG': 2,

'log_count/INFO': 10,

'memusage/max': 56266752,

'memusage/startup': 56266752,

'response_received_count': 2,

'robotstxt/request_count': 1,

'robotstxt/response_count': 1,

'robotstxt/response_status_count/200': 1,

'scheduler/dequeued': 1,

'scheduler/dequeued/memory': 1,

'scheduler/enqueued': 1,

'scheduler/enqueued/memory': 1,

'start_time': datetime.datetime(2020, 11, 3, 4, 56, 38, 348343)}

2020-11-02 23:56:38 [scrapy.core.engine] INFO: Spider closed (finished)

The line that starts with DEBUG: Crawled (200) is good news, as it tells us that the spider was

able to crawl the website we were after. The number in parentheses is the HTTP status code that

Scrapy received in response of its request to access that page. 200 means that the request was successful

and that data (the actual HTML content of that page) was sent back in response.

However, we didn’t do anything with it, because the parse method in our spider is currently empty.

Switching back to our ifabios.py browser tab, let’s change that by editing the spider’s parse method as follows:

def parse(self, response):

with open("test.html", 'wb') as file:

file.write(response.body)

Now, if we go back to the command line and run our spider again

scrapy crawl ifabios

we should get similar debugging output as before, but there should also now be a file called

test.html in our project’s root directory:

ls -F

ifabios/ scrapy.cfg test.html

We can check that it contains the HTML from our target URL:

head test.html

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<!--[if lt IE 9]>Some features of the Institute's website may not function properly with this version of Internet Explorer. Please consider updating your browser by <a href="http://windows.microsoft.com/en-us/internet-explorer/download-ie">clicking here</a>. <![endif]-->

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width">

<meta name="description" content="The Institute: your destination for the past, present, and future of art.">

<!-- OG Tags -->

<meta property="og:image" content="http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/images/headerImages/header-Fall.jpg" />

Defining which elements to scrape using XPath

Now that we know how to access the content of the web page with the list of IFA faculty, the next step is to extract the information we are interested in, in that case the URLs pointing to the detail pages for each faculty member.

Using the techniques we have learned earlier, we can start by looking at the source code for our target page by using either the “View Source” or “Inspect” functions of our browser. Here is an excerpt of that page:

(...)

<div class="mainContent" id="MainContent" role="main">

<h1 class="heading">The Institute of Fine Arts Faculty</h1>

<h2 class="subheading">Academic Administration</h2>

<table role="presentation">

<tr>

<td style="width:120px;" class="contentFaculty"><img src="../images/faculty-thumbs/poggi-thumb.jpg" alt="" width="100" height="100"></td>

<td class="contentFaculty"><a href="faculty/poggi.htm">Christine Poggi </a><br>

<span class="italic">Judy and Michael Steinhardt Director; Professor of Fine Arts</span> <br>

<span class="greycontent">Fields of study: Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Art, Contemporary Art</span></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td class="contentFaculty"><img src="../images/faculty-thumbs/sullivan-thumb.jpg" alt="" width="100" height="100"></td>

<td class="contentFaculty"><a href="faculty/sullivan.htm" >Edward J. Sullivan</a> <span class="italic">(on sabbatical spring 2022)</span><br>

<span class="italic">Deputy Director; Helen Gould Shepard Professor in the History of Art; <br>

The

Institute of Fine Arts and College of Arts and Sciences</span><br>

<span class="greycontent">Fields of study: Latin American (including Brazilian) and Caribbean art, 17th century to present; Latinx art; art of the Iberian Peninsula; contemporary art</span></td>

</tr>

(...)

There are different strategies to target the data we are interested in. One of them is to identify

that the URLs are inside td elements of the class contentFaculty.

We recall that the XPath syntax to access all such elements is //td[@class='contentFaculty'], which we can

try out in the browser console:

> $x("//td[@class='contentFaculty']")

Once we were able to confirm that we are targeting the right cells, we can expand our XPath query

to only select the href attribute of the URL:

> $x("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href")

Note that for this page, we’ll use the double slash in front of the a element because in a couple of instances, a <p> HTML element has snuck between the <td> and <a> elements. This xpath expression returns an array of objects:

$x("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href")

(58) [href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href, href]

Debugging using the Scrapy shell

As we learned in the previous section, using the browser console and the $x() syntax can be useful to make sure

we are selecting the desired elements using our XPath queries. But it is not the only way. Scrapy provides a similar

way to test out XPath queries, with the added benefit that we can then also debug how to further work on those

queries from within Scrapy.

This is achieved by calling the Scrapy shell from the command line:

scrapy shell https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm

which launches a Python console that allows us to type live Python and Scrapy code to

interact with the page which Scrapy just downloaded from the provided URL. We can see that we are inside an

interactive python console because the prompt will have changed to >>>:

(similar Scrapy debug text as before)

2020-11-03 00:25:29 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm> (referer: None)

2020-11-03 00:25:30 [asyncio] DEBUG: Using selector: EpollSelector

[s] Available Scrapy objects:

[s] scrapy scrapy module (contains scrapy.Request, scrapy.Selector, etc)

[s] crawler <scrapy.crawler.Crawler object at 0x7fbf676d21d0>

[s] item {}

[s] request <GET https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm>

[s] response <200 https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm>

[s] settings <scrapy.settings.Settings object at 0x7fbf672e0990>

[s] spider <DefaultSpider 'default' at 0x7fbf66e29510>

[s] Useful shortcuts:

[s] fetch(url[, redirect=True]) Fetch URL and update local objects (by default, redirects are followed)

[s] fetch(req) Fetch a scrapy.Request and update local objects

[s] shelp() Shell help (print this help)

[s] view(response) View response in a browser

2020-11-03 00:25:30 [asyncio] DEBUG: Using selector: EpollSelector

In [1]:

We can now try running the XPath query we just devised against the response object, which in Scrapy

contains the downloaded web page. Next to where your terminal shows In [1]: type the following:

response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href")

This will return a bunch of Selector objects (one for each URL found):

<Selector xpath="//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href" data='faculty/poggi.htm'>,

<Selector xpath="//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href" data='faculty/sullivan.htm'>,

<Selector xpath="//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href" data='faculty/ellis.htm'>,

<Selector xpath="//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href" data='faculty/ellis.htm'>,

<Selector xpath="//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href" data='faculty/thomas.htm'>

...

Those objects are pointers to the different element in the scraped page (href attributes) as

defined by our XPath query. You might notice some duplicates, but we’ll take care of this later. To get to the actual content of those elements (the text of the URLs),

we can use the extract() method. A variant of that method is extract_first() which does the

same thing as extract() but only returns the first element if there are more than one. Let’s try this in scrapy shell:

response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href").extract_first()

returns

'faculty/poggi.htm'

Dealing with relative URLs

Looking at this result and at the source code of the page, we realize that the URLs are all relative to that page. They are all missing part of the URL to become absolute URLs, which we will need if we want to ask our spider to visit those URLs to scrape more data. We could prefix all those URLs with

https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/to make them absolute, but since this is a common occurence when scraping web pages, Scrapy provides a built-in function to deal with this issue.To try it out, still in the Scrapy shell, let’s first store the first returned URL into a variable:

testurl = response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href").extract_first()Then, we can try passing it on to the

urljoin()method:response.urljoin(testurl)which returns

'https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/poggi.htm'We see that Scrapy was able to reconstruct the absolute URL by combining the URL of the current page context (the page in the

responseobject) and the relative link we had stored intesturl. Make sure to typeexit()in your terminal window to quit the Scrapy shell.

Extracting URLs using the spider

Armed with the correct query, we can now update our spider accordingly. The parse

method returns the contents of the scraped page inside the response object. The response

object supports a variety of methods to act on its contents:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

xpath() |

Returns a list of selectors, each of which points to the nodes selected by the XPath query given as argument |

css() |

Works similarly to the xpath() method, but uses CSS expressions to select elements. |

Those methods will return objects of a different type, called selectors. As their name implies,

these objects are “pointers” to the elements we are looking for inside the scraped page. In order

to get the “content” that the selectors are pointing to, the following methods should be used:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

extract() |

Returns the entire contents of the element(s) selected by the selector object, as a list of strings. |

extract_first() |

Returns the content of the first element selected by the selector object. |

re() |

Returns a list of unicode strings within the element(s) selected by the selector object by applying the regular expression given as argument. |

re_first() |

Returns the first match of the regular expression |

Know when to use

extract()The important thing to remember is that

xpath()andcss()returnselectorobjects, on which it is then possible to apply thexpath()andcss()methods a second time in order to further refine a query. Once you’ve reached the elements you’re interested in, you need to callextract()orextract_first()to get to their contents as string(s).Whereas

re()returns a list of strings, and therefore it is no longer possible to applyxpath()orcss()to the results ofre(). Since it returns a string, you don’t need to useextract()there.

Since we have an XPath query we know will extract the URLs we are looking for, we can now use

the xpath() method and update the spider accordingly. Let’s go back to the ifabios.py tab we have open and continue tweaking the parse method.

def parse(self, response):

for url in response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href").extract():

print(response.urljoin(url))

Looping through results

Why are we using

extract()instead ofextract_first()in the code above? Why is theforclause?Solution

We are not only interested in the first extracted URL but in all of them.

extract_first()only returns the content of the first in a series of selected elements, whileextract()will return all of them in the form of an array.The

forsyntax allows us to loop through each of the returned elements one by one.

We can now run our new spider:

scrapy crawl ifabios

which produces a result similar to:

2017-02-26 23:06:10 [scrapy.utils.log] INFO: Scrapy 1.3.2 started (bot: ifafaculty)

(...)

2020-11-03 00:38:23 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm> (referer: None)

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/poggi.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/sullivan.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/thomas.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/lubar.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/cohen.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/crow.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/eisler.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/flood.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/hay.htm

http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/howley.htm

http://www.n

(...)

2020-11-03 00:38:23 [scrapy.core.engine] INFO: Spider closed (finished)

We can now pat ourselves on the back, as we have successfully completed the first stage of our project by successfully extracing all URLs leading to the faculty profiles!

Limit the number of URL to scrape through while debugging

We’ve seen by testing the code above that we are able to successfully gather all URLs from the list of MPPs. But while we’re working through to the final code that will allow us the extract the data we want from those pages, it’s probably a good idea to only run it on a handful of pages at a time.

This will not only run faster and allow us to iterate more quickly between different revisions of our code, it will also not burden the server too much while we’re debugging. This is probably not such an issue for a couple of hundred of pages, but it’s good practice, as it can make a difference for larger scraping projects. If you are planning to scrape a massive website with thousands of pages, it’s better to start small. Other visitors to that site will thank you for respecting their legitimate desire to access it while you’re debugging your scraper…

An easy way to limit the number of URLs we want to send our spider to is to take advantage of the fact that the

extract()method returns a list of matching elements. In Python, lists can be sliced using thelist[start:end]syntax and we can leave out either thestartorenddelimiters:list[start:end] # items from start through end-1 list[start:] # items from start through the rest of the array list[:end] # items from the beginning through end-1 list[:] # all itemsWe can therefore edit our

parsemethod thusly to only scrape the first five URLs:def parse(self, response): for url in response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href").extract()[:5]: print(response.urljoin(url))Note that this only works if there are at least five URLs that are being returned, which is the case here.

Recursive scraping

Now that we were successful in harvesting the URLs to the detail pages, let’s begin by editing our spider to instruct it to visit those pages one by one.

For this, let’s begin by changing our parse method a bit by creating a full_url variable and using the urljoin function. We’ll also add a bit that tells Scrapy to scrape the URL in the ‘full_url’ variable and calls the ‘get_details() method below with the content of this URL. Finally, let’s define our new method get_details that we want to run on the detail pages. We’re going to add a parameter here, dont_filter=True, because of the way this site is set up (the original example in this lesson did not require this).

def parse(self, response):

for url in response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href").extract()[:5]:

full_url = response.urljoin(url)

print("Found URL: "+full_url)

yield scrapy.Request(full_url, callback=self.get_details, dont_filter=True)

def get_details(self, response):

print("Visited URL: "+response.url)

If we now run our spider again:

scrapy crawl ifabios

We should see the result of our print statements intersped with the regular Scrapy

debugging output, something like:

...

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/poggi.htm

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/sullivan.htm

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/thomas.htm

2020-11-03 00:47:23 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/thomas.htm> (referer: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm)

2020-11-03 00:47:23 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm> (referer: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm)

2020-11-03 00:47:23 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm> (referer: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm)

2020-11-03 00:47:23 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/poggi.htm> (referer: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm)

2020-11-03 00:47:23 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/sullivan.htm> (referer: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm)

Visited URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/thomas.htm

Visited URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm

Visited URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm

Visited URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/poggi.htm

Visited URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/sullivan.htm

2020-11-03 00:47:23 [scrapy.core.engine] INFO: Closing spider (finished)

We’ve truncated the results above to make it easier to read, but on your console

you should see that all 5 URLs (remember, we are limiting the number of URLs to scrape

for now) have been first “found” (by the parse() method) and then “visited”

(by the get_details() method).

Asynchronous requests

If you look closely at the output of the code we’ve just run, you might be surprised to see that the “Found URL” and “Visited URL” statements didn’t necessarily get printed out one after the other, as we might expect.

The reason this is so is that Scrapy requests are scheduled and processed asynchronously. This means that Scrapy doesn’t need to wait for a request to be finished and processed before it runs another or do other things in the meantime. This is more efficient than running each request one after the other, and it also allows for Scrapy to keep working away even if some requests fails for whatever reason.

This is especially advantageous when scraping large websites. Depending on the resources of the computer on which Scrapy runs, it can scrape hundreds or thousands of pages simultaneously.

If you want to know more, the Scrapy documentation has a page detailing how the data flows between Scrapy’s components .

Scrape the detail pages

Now that we are able to visit each one of the detail pages, we should work on getting the data that we want out of them. In our example, we are primarily looking to extract the following details:

- Faculty bio

There is other interesting content, but unfortunately, it looks like the content of those pages is not consistent.

To simplify for this exercise, we are going to stop at the first paragraph of the faculty bio section, although in a real life scenario we might be interested in writing more precise queries to make sure we are collecting the right information.

Scrape faculty names and bios

Write XPath queries to scrape the name and first paragraph of the faculty bio displayed on each of the detail pages that are linked from the IFA faculty page.

Try out your queries on a handful of detail pages to make sure you are getting consistent results.

Tips:

- Look at the source code and try out XPath your queries until you find what you are looking for.

- You can either use the browser console or the Scrapy shell mode (see above) to try out your queries.

- The syntax for selecting an element like

<div class="mytarget">isdiv[@class = 'mytarget'].- The syntax to select the value of an attribute of the type

<element attribute="value">iselement/@attribute.Solution

This returns an array of paragraphs (using the Scrapy shell):

scrapy shell "https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/poggi.htm" >>> response.xpath("//div[@class='statement']/article/p/text()").extract()['Much of my research has focused on early twentieth-century European avant-gardes, the invention of collage and constructed sculpture, the rise of abstraction, and the relationship of art to emerging forms of labor, technology, and new media. Iam also interested in the interplay of text and image, the representation of the crowd, and the engagement with theater and performance in modern art from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. The issues taken up in my work on the early-twentieth century have often overflowed and expanded into related essays on contemporary art. In general, I prefer to think ofthe modern/contemporary period without fixed chronological or geographical boundaries and to see how issues or ideas may be elaborated or developed over time and across borders in new and surprising ways.\xa0 I find that my work on the early twentieth-century avant-gardes informs and enriches my perspective on contemporary art and vice versa.', 'My first book, ', ...]By using

extract_first(), we can grab only the first paragraph (using the Scrapy shell):scrapy shell "https://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/poggi.htm" >>> response.xpath("//div[@class='statement']/article/p/text()").extract_first()'Much of my research has focused on early twentieth-century European avant-gardes, the invention of collage and constructed sculpture, the rise of abstraction, and the relationship of art to emerging forms of labor, technology, and new media. I am also interested in the interplay of text and image, the representation of the crowd, and the engagement with theater and performance in modern art from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. The issues taken up in my work on the early-twentieth century have often overflowed and expanded into related essays on contemporary art. In general, I prefer to think of the modern/contemporary period without fixed chronological or geographical boundaries and to see how issues or ideas may be elaborated or developed over time and across borders in new and surprising ways.\xa0 I find that my work on the early twentieth-century avant-gardes informs and enriches my perspective on contemporary art and vice versa.'And the following returns an array of names. In this case, just one value is in the list. Note that a wildcard is helpful, because some faculty pages use the “heading” attribute in

<h1>element, and others use a<p>element!response.xpath("//div[@id='MainContent']//*[@class='heading']/text()").extract()['Christine Poggi']

Using Regular Expressions with XPath

In combination with XPath queries, it is also possible to use Regular Expressions to scrape the contents of a web page. For the sake of time, we won’t do this today, but you can learn more about how to do this by taking a look at the Library Carpentries official version of this lesson

Once we have found XPath queries to run on the detail pages and are happy with the result,

we can add them to the get_details() method of our spider. We will also add the normalize-space XPath function, which we saw the Scraper extension lesson earlier.

import scrapy

class IfabiosSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = 'ifabios'

allowed_domains = ['www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/']

start_urls = ['http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm']

def parse(self, response):

for url in response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href").extract()[:5]:

full_url = response.urljoin(url)

print("Found URL: "+full_url)

yield scrapy.Request(full_url, callback=self.get_details,dont_filter=True)

def get_details(self, response):

print("Visited URL: "+response.url)

faculty_name = response.xpath("normalize-space(//div[@id='MainContent']//*[@class='heading']/text())").extract_first()

brief_bio = response.xpath("normalize-space(//div[@class='statement']/article/p/text())").extract_first()

print("Found name and bio: " + faculty_name +"----" + brief_bio)

Running our scraper again

scrapy crawl ifabios

produces something like

...

2020-11-03 12:07:05 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm> (referer: None)

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/poggi.htm

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/sullivan.htm

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/ellis.htm

Found URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/thomas.htm

2020-11-03 12:07:05 [scrapy.core.engine] DEBUG: Crawled (200) <GET http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/thomas.htm> (referer: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm)

Visited URL: http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/thomas.htm

Found name and bio: Thelma K. Thomas----Within my specialized fields of Late Antique, Early Christian, Byzantine, and Eastern Christian art, architecture, and archaeology, my present primary research interests are material and visual culture, materiality, and historiography. Topics of recent research include dress and identity, ancient and modern art commerce, the luxury arts, and visual rhetoric, especially as they reveal intercultural contact and syncretistic expressions. Recurrent subjects are sculpture, textiles, wall and panel painting, and private devotional, particularly monastic, arts. My current book project on painted commemorative portraits in Late Antique Egyptian monasticism, emphasizing the construction, maintenance, and presentation of identity through dress has rekindled my interest in funerary arts, the subject of my first single-author book,

...

We appear to be getting somewhere! The last step is doing something useful with the scraped data instead of printing it out on the terminal. For this, we’ll use Scrapy Items.

Using Items to store scraped data

Scrapy conveniently includes a mechanism to collect scraped data and output it

in several different useful ways. It uses objects called Items. Those are akin

to Python dictionaries in that each Item can contain one or more fields to

store individual data element. Another way to put it is, if you visualize the

data as a spreadsheet, each Item represents a row of data, and the fields within

each item are columns.

Before we can begin using Items, we need to define their structure. Let’s edit the items.py file that Scrapy has created for us when we

first created our project. If you are using JupyterHub, open this file in a new tab by navigating to the second ifafaculty folder: ifafaculty/ifafaculty/items.py

Scrapy has pre-populated this file with an empty “IfabiosItem” class:

import scrapy

class IfafacultyItem(scrapy.Item):

# define the fields for your item here like:

# name = scrapy.Field()

pass

Let’s add a few fields to store the data we aim to extract from the detail pages for each politician:

import scrapy

class IfafacultyItem(scrapy.Item):

# define the fields for your item here like:

faculty_name = scrapy.Field()

brief_bio = scrapy.Field()

Then save this file. We can then edit our spider one more time:

import scrapy

from ifafaculty.items import IfafacultyItem # We need this so that Python knows about the item object

class IfabiosSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = 'ifabios'

allowed_domains = ['www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/']

start_urls = ['http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm']

def parse(self, response):

for url in response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href").extract()[:5]:

full_url = response.urljoin(url)

print("Found URL: "+full_url)

yield scrapy.Request(full_url, callback=self.get_details,dont_filter=True)

def get_details(self, response):

item = IfafacultyItem()

item['faculty_name'] = response.xpath("normalize-space(//div[@id='MainContent']//*[@class='heading']/text())").extract_first()

item['brief_bio'] = response.xpath("normalize-space(//div[@class='statement']/article/p/text())").extract_first()

# Return that item to the main spider method:

yield item

We made two significant changes to the file above:

- We’ve included the line

from ifafaculty.items import IfafacultyItemat the top. This is required so that our spider knows about theIfafacultyItemobject we’ve just defined. - We’ve also replaced the

printstatements inget_details()with the creation of anIfafacultyItemobject, in which fields we are now storing the scraped data. The item is then passed back to the main spider method using theyieldstatement.

If we now run our spider again:

scrapy crawl ifabios

we see something like

...

2020-11-03 12:27:54 [scrapy.core.scraper] DEBUG: Scraped from <200 http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty/sullivan.htm>

{'brief_bio': 'My intellectual formation at the IFA in Early Modern art with a '

'concentration on southern Europe was an excellent preparation '

'for my later studies in the art of the Americas. I began '

'teaching at NYU in the early 1980s at the Department of Art '

'History where I also served as Chair for some thirteen years. '

'From 2003 to 2009 I served as FAS Dean for the Humanities while '

'continuing my teaching and research. I was invited to teach at '

'the IFA in 1991, offering a seminar on Mexican art of the '

'twentieth century. The IFA became my principal department in '

'2010 and I currently teach two graduate courses (seminars and '

'lecture courses) and one undergraduate course per year. I have '

'a long-standing interest in the arts and visual cultures of the '

'Americas with a particular concentration in the Spanish and '

'Portuguese speaking countries of Latin America and the '

'Caribbean. Looking at the greater importance of the diasporas '

'(African, Asian) to the Americas also deeply informs my work as '

'does a keen interest in modern and contemporary Latinx art '

'about which I have written extensively. Nonetheless what '

'characterizes my work and teaching perhaps more than anything '

'else is my desire to cross borders and look beyond the confines '

'of the places I examine. I am interested in socio-political '

'approaches to art history combined with broader theoretical '

'concerns. In all of my work the object of art is a principal '

'focus of interest. My 2007 book\xa0',

'faculty_name': 'Edward J. Sullivan'}

...

We see that Scrapy is dumping the contents of the items within the debugging output using a syntax that looks a lot like JSON.

But let’s now try running the spider with an extra -o (‘o’ for ‘output’) argument that

specifies the name of an output file with a .csv file extension:

scrapy crawl ifabios -o output.csv

This produces similar debugging output as the previous run, but now let’s look inside the

directory in which we just ran Scrapy and we’ll see that it has created a file called

output.csv, and when we try looking inside that file, we see that it contains the

scraped data, conveniently arranged using the Comma-Separated Values (CSV) format, ready

to be imported into our favourite spreadsheet!

cat output.csv

Returns

brief_bio,faculty_name

"Within my specialized fields of Late Antique, Early Christian, Byzantine, and Eastern Christian art, architecture, and archaeology, my present primary research interests are material and visual culture, materiality, and historiography. Topics of recent research include dress and identity, ancient and modern art commerce, the luxury arts, and visual rhetoric, especially as they reveal intercultural contact and syncretistic expressions. Recurrent subjects are sculpture, textiles, wall and panel painting, and private devotional, particularly monastic, arts. My current book project on painted commemorative portraits in Late Antique Egyptian monasticism, emphasizing the construction, maintenance, and presentation of identity through dress has rekindled my interest in funerary arts, the subject of my first single-author book,",Thelma K. Thomas

By changing the file extension to .json or .xml we can output the same data

in JSON or XML format.

Refer to the Scrapy documentation

for a full list of supported formats.

Now that everything looks to be in place, we can finally remove our limit to the number

of scraped elements by deleting [:5]…

import scrapy

from ifafaculty.items import IfafacultyItem # We need this so that Python knows about the item object

class IfabiosSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = 'ifabios'

allowed_domains = ['www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/']

start_urls = ['http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/people/faculty.htm']

def parse(self, response):

for url in response.xpath("//td[@class='contentFaculty']//a/@href").extract():

full_url = response.urljoin(url)

print("Found URL: "+full_url)

yield scrapy.Request(full_url, callback=self.get_details,dont_filter=True)

def get_details(self, response):

item = IfafacultyItem()

item['faculty_name'] = response.xpath("normalize-space(//div[@id='MainContent']//*[@class='heading']/text())").extract_first()

item['brief_bio'] = response.xpath("normalize-space(//div[@class='statement']/article/p/text())").extract_first()

# Return that item to the main spider method:

yield item

… and run our spider one last time:

scrapy crawl ifabios -o output.csv

Add other data elements to the spider

Try modifying the spider code to add more data extracted from the IFA faculty detail page. Remember to edit the Item definition to allow for all extracted fields to be taken care of.

Congratulations! You are now ready to write your own spiders!

Reference

Key Points

Scrapy is a Python framework that can be use to scrape content from the web.

A Scrapy project is a set of configuration files and pieces of code that tell Scrapy what to do.

In Scrapy, a “Spider” is the code that tells it what to do on a specific website.

A Scrapy project can have more than one spider but needs at least one.

With Scrapy, we can use XPath, CSS selectors and Regular Expressions to define what elements to scrape from a page.

Extracted data can be stored in “Item” objects. Such objects must be defined before they can be used.

Scrapy will automatically stored extracted data in CSS, JSON or XML format based on the file extension given in the -o option.